Hunters and farmers

Documentary photography is probably one of the genres that has developed the most throughout the history of photography.

I should start by defining what we mean by documentary photography: it is a photographic genre that, based on more or less thorough prior research, portrays a social, natural, cultural reality, and so on. It has points of connection with photojournalism, of course, but the main difference is that it is not so closely tied to current events, to the here and now, nor is it primarily intended for publication in the news media. Documentary photography develops at a slower pace and is not necessarily linked to novelty: any subject that interests the author can be the basis for a documentary project.

But because of that connection between documentary photography and what happens in the world, as society has evolved, the principles on which it operates have also changed. In a simplified way, I could distinguish three broad “phases,” for lack of a better term.

The origins: social denunciation

The first documentary photographers wanted to raise awareness in society, to denounce unjust situations. To change the world through photography. There are already examples by the end of the 19th century, among which Jacob Riis stands out above all: a Danish-born policeman who emigrated to the United States and, with his 1890 book How the Other Half Lives, denounced the living conditions in New York’s slums. Even President Teddy Roosevelt (who had been chief of police in the city) took an interest in the work, which indeed led to nationwide reforms.

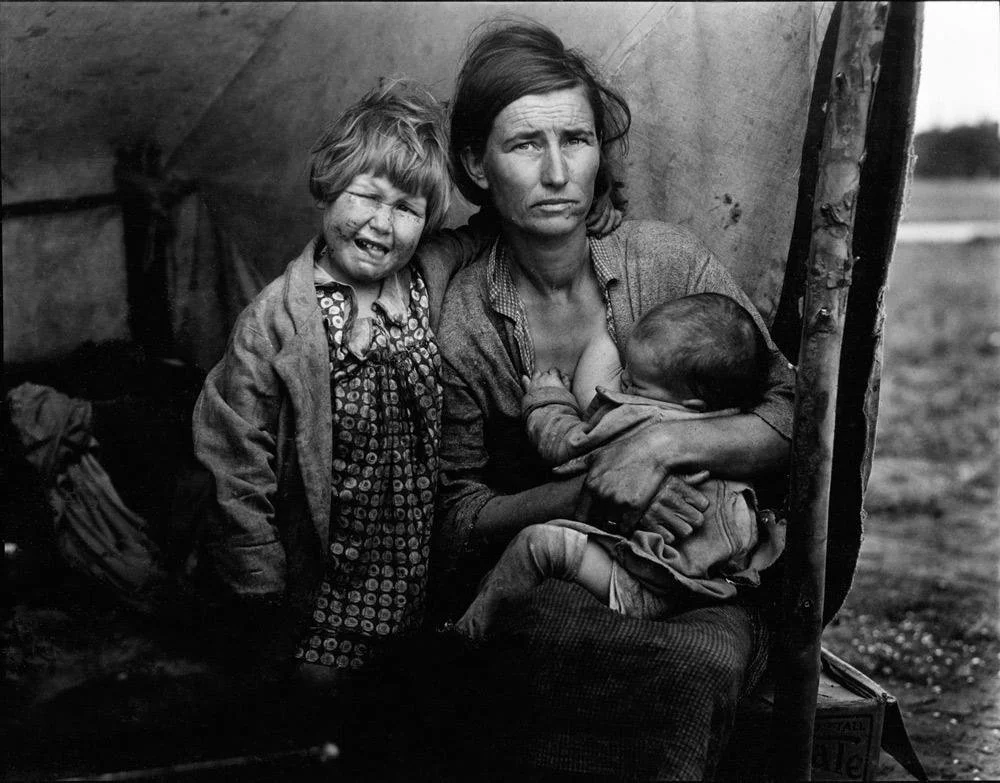

Riis was a pioneer, followed by others such as Lewis Hine, who was especially concerned with child labor and the conditions of immigrants. Or the photographic project commissioned by the FSA after the crash of 1929 to portray the difficult situation of rural America. We are talking about people like Walker Evans or Dorothea Lange. And yes, I could show that photo, but I actually prefer this one:

Dorothea Lange, from the Migrant Mother series (Florence Owens Thompson and two of her children). 1936. Oakland Museum, via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain image.

The fundamental characteristic of this first documentary photography was realism. Aesthetics mattered, of course, but the essential thing was to show what was happening without intervening in it.

At this point you’re probably wondering why this article is titled “hunters and farmers.” Bear with me, it’s coming.

New Documents changes the rules of the game

1967. The director of the Department of Photography at MoMA, John Szarkowski—the man with the sharpest eye of the 20th century, and the only one who could really pull off a moustache—organized an exhibition showcasing the work of three young photographers who were not so much trying to change the world as to observe it. We’re talking about Diane Arbus, Lee Friedlander, and Garry Winogrand, little known at the time, legends today. The exhibition was not without controversy, since the shift away from social critique toward the… what? the everyday? the banal?… was not well understood.

The melon had already been cracked open with the 1958 publication of Robert Frank’s legendary book The Americans, which at first ruffled feathers because some felt it distorted the “true American values.” The MoMA exhibition finished freeing documentary photography from its ties to social critique and opened it up to more subjective approaches, where everything could fit: irony, violence, intimacy…

From the 1970s onward, we see a different kind of work based on the mundane, as in the case of Stephen Shore and William Eggleston, or even the intimate, like Nan Goldin. This trend was not limited to the United States, of course: the Provoke group in Japan, Martin Parr in the UK, Cristina García-Rodero or the photographers behind AFAL in Spain…

Well, all the photographers mentioned so far in this article are examples of hunters, according to the definition attributed to Jeff Wall and quoted in Charlotte Cotton’s The Photograph as Contemporary Art. Wall distinguishes two ways of photographing: on the one hand, photographers who come across a scene that interests them and capture it, like a hunter with its prey; on the other hand, the farmers, who plant first in order to later harvest.

And in photographic terms, what does it mean to be a farmer?

It means a kind of documentary photography that intervenes in the scene. It is thought out, organized, prepared. Already in the mid-20th century, voices arose questioning the supposed objectivity of the photographer. Doesn’t the photographer choose what to talk about? Doesn’t the frame include some things and exclude others? Don’t they seek a certain light? Isn’t that already a way of intervening in reality?

In my opinion, undeniably yes. For me, from the moment there is a human being handling the camera, there can be no objectivity. Sure, I get the idea of the aseptic gaze, blah, blah, blah, but photography is subjective—and not even Bernd and Hilla Becher, nor the entire Düsseldorf School, will drag me out of this trench.

New documentary: between reality and artistic expression

The 21st century embraces that active intervention in the scene to build images as an expressive element. It also raises questions that fifty years ago were hardly considered. For example: when photographing a person in a difficult situation (a homeless person, someone with mental illness…), is their suffering being aestheticized? Is it an abuse of power from our privileged vantage point? Honestly, I ask myself this often when I travel. And yes, I usually ask permission, approach, greet and explain. And if the person doesn’t want a photo, I don’t take one. But is there really a relationship of equality? Real consent? I don’t think so.

Thirdly, new documentary also presents a “hybrid” approach between photographing reality and explicitly adding something of the photographer themselves to it: their sexual orientation, their intimate concerns, their family history… One could say we are faced with a mix between the I and the this.

For all these reasons, photographers associated with new documentary are farmers in pure or near-pure form. They build artificial scenes to continue talking about the real issues that concern them, and they draw on every technical and expressive resource at their disposal to create their work. That makes it especially complicated to draw the line today between what is documentary and what is not. The staged photographs of Jeff Wall, for example. Or those of Alec Soth or Rob Hornstra. Or Gregory Crewdson, with his unsettling, quasi-cinematic scenes—are they documentary, or art?

It’s not that documentary and artistic are mutually exclusive, far from it. But for me—and this is a slightly contrarian opinion—it’s hard to separate documentary photography from authenticity. The moment a scene is artificially constructed, no matter how much the author does so in order to talk about a real issue, to me it moves away from documentary photography and closer to artistic photography.

Of course, I’m a hunter through and through, the kind who goes out with spear and club to see if an elephant comes along. If I ever evolve, it will only be to swap the club for a lightweight tripod. At most.

Notes:

The opening image was generated with Sora AI.

This article contains no affiliate links.